High School Student's AI Discovery: 1.5 Million Hidden Cosmic Objects Unlock NASA's Decade of Data

17-year-old Matteo Paz from Caltech developed VARnet, an AI model that processes 53 microseconds per star, uncovering 1.5 million variable objects in NASA's NEOWISE archive and revolutionizing infrared astronomy.

The Problem: 200 Billion Rows of Invisible Data

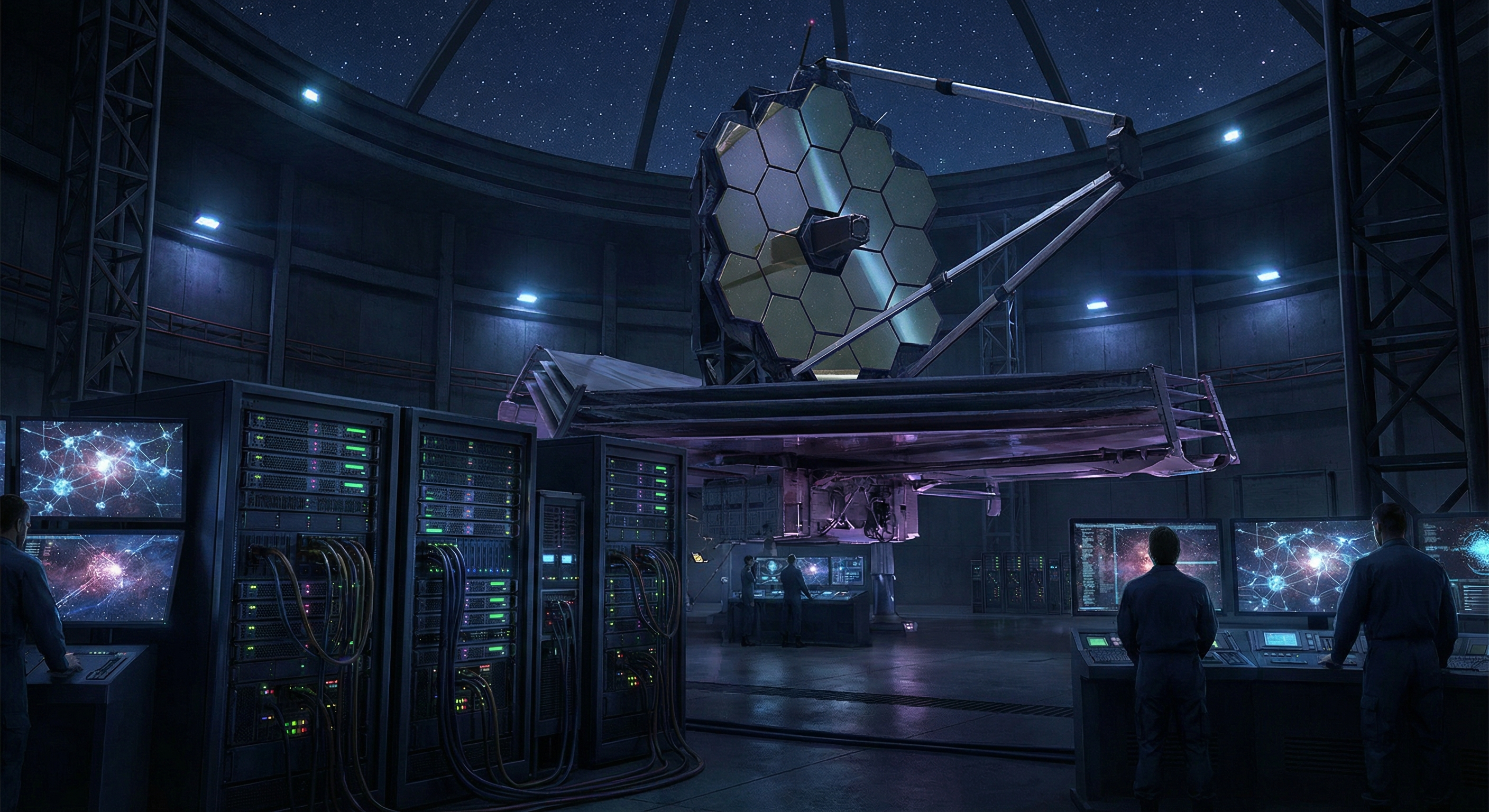

For more than a decade after NASA's NEOWISE telescope began its reactivated mission, one of the most comprehensive infrared surveys of the entire sky sat largely untapped in institutional archives. While the primary asteroid-tracking data was processed, an astronomical treasure trove remained hidden: variable objects like flickering quasars, pulsing stars, and eclipsing binaries buried within 200 billion individual detections.

Davy Kirkpatrick, a Caltech senior research scientist at IPAC (Infrared Processing and Analysis Center), had spent years contemplating this dataset. "At that point, we were creeping up towards 200 billion rows in the table of every single detection that we had made over the course of over a decade," Kirkpatrick explained. The data had grown too large for conventional analysis methods.

His original summer project proposal was modest: analyze a small patch of sky, manually find some variable stars, publish them as proof of concept. Then 17-year-old Matteo Paz from Pasadena High School walked into his laboratory with a different idea entirely.

VARnet: The Model That Runs at 53 Microseconds Per Star

Matteo Paz wasn't your typical high school intern. He had been attending Caltech's public stargazing lectures with his mother since elementary school. By summer 2023, when he joined Kirkpatrick's lab through the university's Summer Research Connection program, he had already completed AP Calculus in eighth grade through Pasadena Unified's accelerated Math Academy and was studying undergraduate-level mathematics.

On his first day, Paz told Kirkpatrick he wanted to publish a paper. Rather than the manual analysis Kirkpatrick had planned, Paz proposed building an AI model to analyze the entire NEOWISE database—all 10.5 years of observations covering the complete sky.

The result was VARnet, a sophisticated three-stage machine learning pipeline designed specifically for astronomical time series data:

- Wavelet Decomposition: Reduces the impact of spurious measurements and noise in the irregular observation patterns

- Modified Discrete Fourier Transform: Extracts periodic features from irregularly sampled light curves, capturing the rhythms of pulsating and eclipsing objects

- Convolutional Neural Networks: Classifies each source into four categories: non-variable, transient events (like supernovae), intrinsic pulsators, or eclipsing binary systems

The performance metrics, published in The Astronomical Journal in peer-reviewed detail, are staggering: VARnet processes each astronomical source in less than 53 microseconds on a GPU with 22 gigabytes of VRAM, achieving an F1 score of 0.91 on a validation set of known variable objects. At that speed, the model can analyze the entire NEOWISE catalog—something that would have taken human astronomers years—in a matter of hours.

Mentorship: The Tennessee Connection

Kirkpatrick's approach to mentoring Paz was deeply informed by his own experience. Growing up in a farming community in Tennessee, his ninth-grade chemistry and physics teacher, Marilyn Morrison, told him and his mother that he had scientific potential and outlined the courses he would need for college. She was, Kirkpatrick said, the reason he became an astronomer.

"I wanted to pass on that same sort of mentoring to someone else and hopefully many someone elses," Kirkpatrick reflected. "If I see their potential, I want to make sure that they are reaching it. I'll do whatever I can to help them out."

That philosophy shaped every decision in the summer project. When Paz proposed the ambitious AI approach, Kirkpatrick didn't dismiss it as too complex for a high school student. Instead, he connected Paz with Caltech researchers Shoubaneh Hemmati, Daniel Masters, Ashish Mahabal, and Matthew Graham—experts in machine learning techniques for astronomy and the analysis of variable objects on different timescales.

Paz acknowledged the impact: "He has allowed an unbridled learning experience. I think that's why I've grown so much as a scientist."

The 1.5 Million Candidates: What They Mean

VARnet flagged 1.5 million potential variable objects in the NEOWISE archive. This figure requires careful interpretation: these aren't 1.5 million confirmed new discoveries in the traditional sense. Each flagged source is a candidate requiring follow-up observation and classification by astronomers.

The breakdown will likely include:

- Known objects with new infrared characterization: Many will be stars and quasars already cataloged in visible wavelengths, now characterized in infrared for the first time

- False positives: Some fraction will prove to be artifacts of the observational process or noise in the data

- Genuinely new detections: A significant subset will be previously unknown quasars, variable stars, eclipsing binaries, and transient events

The full catalog is scheduled for publication in 2025. Once released, it will provide the astronomical community with a dataset large enough to support statistical studies of infrared variability across the entire sky—a capability that has never existed before. Instead of the piecemeal analyses that have characterized infrared variable star research, astronomers will be able to study populations, distributions, and rare phenomena at scale.

Beyond Astronomy: Time Series AI at Scale

Paz, now employed at IPAC while finishing high school, sees applications far beyond the night sky. "The model I implemented can be used for other time domain studies in astronomy, and potentially anything else that comes in a temporal format," he explained.

The implications are significant:

- Financial analysis: Chart analysis and market patterns where information arrives in time series and periodic components are critical

- Environmental monitoring: Atmospheric effects such as pollution, where periodic seasons and day-night cycles play huge roles

- Seismology: Detecting patterns in earthquake precursors or volcanic activity

- Medical diagnostics: Analyzing heart rate variability, EEG patterns, or any biological signal that changes over time

The architecture's ability to handle irregularly sampled data—a common challenge in real-world time series—makes it particularly valuable beyond astronomy. Most time series occur with missing data points, irregular intervals, or varying measurement quality. VARnet was designed from the ground up to handle these realities.

The Democratization of Scientific Discovery

Perhaps the most profound aspect of this story isn't the technical achievement—though that's impressive—but what it represents for the future of scientific research. A high school student, given access to institutional data, mentorship from established researchers, and computational resources, accomplished what professional astronomers had considered a multi-year institutional project.

This democratization is happening across scientific disciplines:

- Open data policies from NASA, ESA, and other space agencies make decades of observations available to anyone with internet access

- Cloud computing platforms provide GPU resources affordable even for students

- Open-source machine learning frameworks (PyTorch, TensorFlow) lower the barrier to implementing sophisticated models

- Pre-print servers and open-access journals accelerate knowledge sharing

The collaboration also revealed constraints that institutional researchers hadn't fully appreciated. NEOWISE's observational rhythm—scanning in great circles centered on the Sun—means it cannot systematically detect objects that flash once and fade, or those that change gradually over years. Some classes of variable phenomena will remain invisible to any automated survey based on NEOWISE data alone. Understanding these limitations required both Paz's fresh perspective and the institutional knowledge of the Caltech team.

What Comes Next

The catalog's publication in 2025 will mark the beginning, not the end. Astronomers worldwide will use VARnet's candidate list to:

- Conduct targeted follow-up observations with ground-based and space telescopes

- Cross-reference with other surveys (Gaia, TESS, Vera Rubin Observatory) to build multi-wavelength pictures of variable objects

- Study the statistical properties of different variable populations

- Search for rare phenomena like unusual binary configurations or exotic transient events

For Paz personally, the project has opened doors. Now working at IPAC while completing high school, he's already thinking about extending VARnet's capabilities and exploring new applications. Kirkpatrick's mentorship model—treating a talented high school student as a genuine research collaborator rather than an intern to be given simplified tasks—has produced exactly what he hoped: a young scientist reaching their potential and contributing meaningfully to their field.

The Bigger Picture: AI as Scientific Amplifier

This breakthrough exemplifies AI's role in modern science: not replacing human insight but amplifying it exponentially. The NEOWISE data existed for over a decade, accessible to any astronomer. What changed wasn't the availability of information but the tools to process it at scale.

Machine learning models like VARnet act as scientific amplifiers, letting researchers ask questions that were previously computationally infeasible. The pattern repeats across disciplines:

- Particle physics: ML models sift through petabytes of Large Hadron Collider data to identify rare events

- Genomics: Deep learning predicts protein structures and identifies disease markers in massive genetic datasets

- Climate science: Neural networks detect patterns in decades of satellite observations, revealing connections invisible to traditional analysis

- Drug discovery: AI screens millions of molecular candidates in silico before expensive lab work begins

In each case, human expertise guides the questions, interprets the results, and provides domain knowledge to shape the models. But AI handles the scale—processing more data, faster, than any human team could manage.

Conclusion: Mapping the Invisible

"I mapped the invisible," is how Paz described his work—a fitting summary for a project that revealed 1.5 million objects hidden in plain sight within publicly available data. The story is about more than astronomy or AI. It's about what becomes possible when we give talented young people access to powerful tools, pair them with generous mentors, and trust them to tackle genuinely difficult problems.

As Kirkpatrick reflected on the experience, he emphasized the importance of recognizing potential: "If I see their potential, I want to make sure that they are reaching it." That philosophy—combined with open data, accessible computational resources, and machine learning frameworks anyone can use—is democratizing scientific discovery in ways that would have seemed impossible a generation ago.

The 1.5 million candidate variable objects are just the beginning. VARnet's real legacy may be demonstrating that the next major scientific breakthrough could come from anywhere—including a high school student in Pasadena with access to NASA data and an AI model running at 53 microseconds per star.